Introduction

In part one of the series, we evidenced a growing adoption of 3D modelling and model making for community engagement. There is a greater push for design quality within the industry, and this has been supported by the UK Government (see White Paper on Planning for the Future) which may see 3D visualisations of current and the future built environments take a more permanent and prominent role within the planning process, including public consultation.

In the second part of a series, this article presents the 3D models of larger geographic areas, such as neighbourhoods or cities, that have the potential to support public consultations. No longer confined to the realms of the Gaming Industry, built environment professionals increasingly use 3D visualisations in Urban Planning. Cities such as Manchester or Newcastle/Gateshead hold large-scale models of their city centres.

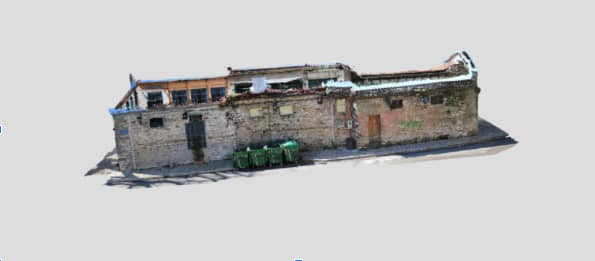

The abundant availability of images of the world and computing power means that we can now more easily create 3D models from photos. This is called ‘photogrammetry’ and has been popular amongst 3D model creation. This is done by compiling 3D models by 2D images by a computer. It has been used by historians, designers and architects who have been able to capture objects who would like to present objects with a rounded perspective. For instance the Tredwell dress from the Merchant House. Professionals in urban planning have also begun developing 3D models as they collaborate with 3D modelers (or 3D artists), but unlike the humble dress, develop a 3D model on a much grander scale.

This article will look at the tools and services available for organisations who want to capture the current environment within a 3D model. Reviewing these options, I conclude with the advantages and disadvantages of using such services for engagement. Specifically, I focus on photogrammetry as a solution to environmental, heritage, architectural, archaeological, ecological and community consultations to aid clarification before any conceptual designs are devised. Beginning with what is considered before the creation of a photogrammetric 3D model for a consultation. We then explore the requirements that produce a 3D model via, photogrammetry, aerial photogrammetry, and laser scanning surveying. We can observe that these methods are interconnected, but not identical.

Considerations for using 3D models in public consultations

First, it is crucial to understand that this technology is not currently standard in public engagement; and that there are a variety of ways and approaches to creating a 3D model. Weighing up the use of a 3D photogrammetric model is also important. If you commission a model of the site context for instance, on a smaller scale it might not be longer cost prohibitive but might instead have larger a social value for the community (i.e specific historical sites.) This might only require a smaller drone or use camera images on a building scale, but will still require a specialist to bring in their understanding of photogrammetry to capture the object.

Secondly, when creating 3D models for a project, it is essential to follow criteria that will match the requirements of the use of the model, for example, in citizen engagement and the public stakeholders that you are interested in engaging with.

Finally, it is important to note the quality of the 3D model and if it meets certain standards that will aid the public consultation. At minimum, the model will ideally help provide context to your project to help with the following:

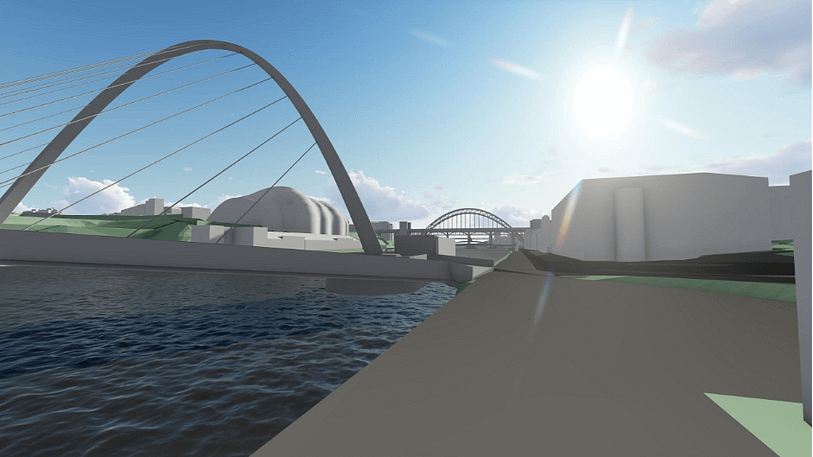

Even a model with a low graphical spec, such as a low resolution or lack of textures, the model should retain a recognisable silhouette of the built environment. For example (see above) it should enable easy recognition of key landmarks to aid with navigation. This is key towards effective communication and public engagement, as so for the public to interpret the model and offer insights into the area.

What is photogrammetry?

Photogrammetry acts as a reverse Camera. It restructures a wide range of still images into a model by looking for overlaps in the visual details in each photo.

There is photogrammetry that focuses on smaller objects, such as close-range photogrammetry (one DSLR camera or mobile phone camera for smaller objects), camera arrays (several cameras for object reconstruction), and wide-angle photogrammetry (using wide-angle lens or a 360 camera for building interiors or outdoor spaces). Finally there is photogrammetry using images from drones, aircraft, or even satellite images.

3D representation of Trafalgar Square on Google Maps.

When creating photogrammetric based models, they require at least one image per surface and have graphic key details visible in two images. There should be anywhere from 20-250 different visual shots depending on the size and complexity of your object / or building. Generally the more images, the better, as this will make a model mode detailed and accurate, but it will also increase the complexity of the model, which may make it harder to work with.

Various software packages can analyse digital images to create a 3D reconstruction. Some examples include PhotoModeler, Geodetic Systems, Autodesk ReCap and RealityCapture. They are often developed for very different applications, but the good news is that some of them are free of charge.

While some tools perform the process more automatically than others, each approach will usually create errors and require editing manually if a software cannot automatically solve the positions of the photos. This may require an element of training and ideally a specialist on the team who has a degree of experience on the respective method. All going well, these models provide accurate information for planners, developers, designers and architects who can review the captured built environment interactively as a 3D model, rather than via traditional photo images. It can have the benefit of going back to study a site in retrospect even if no longer on site; and it can be a useful input to public engagement.

Different methods to create 3D models from images

Focusing on if photogrammetry is suitable to capture a larger environment for a consultation with the public, it is important to be aware of the various options in making 3D models for currently existing buildings. The following photogrammetric models are created in various methods, from ground based photos, aerial Photogrammetry incl. Laser Scanning. These all create 3D models that can be interacted with on its surface level (i.e viewed at 360 degrees) and the preferred options of photogrammetry amongst professionals and 3D model enthusiasts.

These models will mostly differ from how the 2D imagery is being collected, either from the internet, the ground, aerial photography or laser scanning. This will differ in the level of detail and size of the model.

Self-made photogrammetry

Tools are becoming freely available to create 3D models through a process that relies on photos from standard photo cameras for instance. While this option will have to rely on the expertise of the 3D modeler or software engineer, the ordinary enthusiast is increasingly able to produce models themselves using tools like Blender, and Alice Vision while professionals might prefer Autodesks ReCap Pro. Either way these programmes make a 3D model out of hundreds of pictures of a selected building. The 3D model can then be transferred onto a web viewer in which external servers can then view it. A popular web viewing tool for photogrammetric models is Sketchfab, as many modelers can upload 3D models to share amongst other enthusiasts. Businesses can also purchase use of Sketchfabs web viewer, which is a popular tool for outlets wanting to present items such as furniture without being physically there.

Photogrammetric 3D Point Cloud created with DSLR - Creative Commons (from topometrics.gr)

Simple models are useful for consultation, as it can capture the current imagery of an area. The model would be frozen like a photograph, but navigable. As the model is purely a composition of images, it cannot be edited as a digital model could. Aunty edit that could be made will be mostly cosmetic after the model is created, such as changing colour of the textures or exposure. Any amendments to the built environment would not show in this model, but the model can serve as a backdrop in game-engine based visualisation tools, like Blender.

Reasons this type of 3D model might not be as applied by planners currently stem from issues such as capacity and skill. The process is being done by a 3D modeler who will most likely be an external for-profit company. This means that this 3D modeler will be filled in with the necessary information of the consultation, they will need to capture the imagery and access to this site before they can create the model.

Handheld photogrammetry like the other options will require an external company gathering the imagery / 3D data before pipelining. In many aspects this would be costly for a single building without many external features.

Aerial Photogrammetry

Aerial Photogrammetry is used when an even larger 3D model is required. Often archaeologists will use aerial photography to capture large historical sites, which can either be viewed in 2D or turned into a 3D model for observation. Unlike the method above aerial photography gives professionals the ability to create 3D maps, as well as the 3D model.

Aerial photogrammetry uses aerial images that are acquired by satellite, commercial aircraft or UAV drone to collect images of buildings, structures and terrain for 3D reconstruction. As the air-born data collection can capture a wider area than 3D augmentation from the ground-up, the size of these models will be vastly larger. They will most likely take in details that might need to be later erased in the software like any other aesthetic touch up. Unlike the method above, the project will require a specialist in aerial photography as a drone will be needed to fly a predefined route and capture images consistently for a large area.

The breadth of detail in this method will require more time to compile and finalise the 3D model for viewing. The benefit of this method however, will be that these photographs are likely to be geotagged (i.e a GPS coordinate) and aid the compiling of a 3D map. The software used to compile these maps are more specialised than its grounded alternative. DroneDeploy and Pix4DMapper photogrammetry software for instance have been created with the collaborative team in mind. This can be beneficial if your interest expands from just a public consultation but interweaves with the material required for desktop research.

In fact, companies such as Google and Apple have produced 3D maps using satellite-based images. Reasons this type of 3D model might not be as applied by planners can be due to issues with copyright. Many examples found online rely on image and 3D data provided by Google Maps. Google has made their data online in a viewable form from the public, and effectively many of these examples might be against Google’s terms of service.

Aerial photogrammetry is a much larger model than the ground level option, and therefore much more costly due to the additional aerial hardware needed to capture the imagery data.

Aerial Photogrammetry and Laser Scanning Survey

This approach combines the photogrammetric system with aerial laser captures and relies on data collected by both aerial surveys and laser scanning. Once again acting as a top-down method, as if a large blanket covering the geographic area in question. Unlike the previous method, this relies on an extensive data collection and regular updates for efficiency management. This kind of survey has the highest degrees of accuracy but is also the most expensive.

© Northumbria University (used with permission)

Virtual NewcastleGateshead (VNG), is a model for Newcastle and Gateshead resulting from a joint venture between Northumbria University, Newcastle City Council, and Gateshead Council to create a three-dimensional digital model of Newcastle and Gateshead. The Councils sit on the opposite banks of the River Tyne and therefore was a mutually beneficial risk that could result with a range of applications both urban planning and organising heritage plans.

This has been an effective method for heritage consultations, due to Newcastle’s rich history and striking aesthetic, but such a model can not be overlaid with textual details. The model also requires to be regularly adjusted, as roads are reworked to fit a 21st-century city plan, and pedestrian paths and underpasses are better presented in the model (an issue that results from the top-down data collection.)

Such a model is a workable solution for urban planning in the United Kingdom’s changing environment. Changes to a cities skyline (i.e Hadrian’s Tower in Newcastle) will require additional visual data, collected by an aerial laser and developed into a reworked version of the VNG project. It is a technical solution which requires the support of technical and planning leaders in the area and reaches out to external stakeholders to develop a conversation on the shared environment.

Underlying issues of Aerial Photogrammetry

Photogrammetry relies on techniques to manipulate a large quantity of images into a 3D model. This approach naturally has a number of limitations that currently hamper its use in urban planning.

A photogrammetric model requires a very large number of images, individuals with a certain skill set and at times powerful technical resources that will increase drastically as the level of detail and scope of the model increases. Furthermore these images are collected in a range of different ways but can be restricted by the creator’s own access to that data. When creating models for public engagement, it can be problematic in publishing data that might originate from different places. This can be worked around if organisations have access to their own aerial collection resources. This can be costly, but as seen with the partnership between Gateshead and Newcastle Council can be worked around.

Relying on photogrammetry can create its own issues as these 3D methods are trapped within its aesthetics. They mostly can serve as an input. It would be hard to present a master plan with just the aesthetics of the building project. Certain information within a public engagement needs to be presented, such as light, accessibility, eco-sustainability, and building materials. This means that 3D models of any proposals need to be created separately for use in public engagement. These models are also more in the control of architects, who produce them. Therefore, it can be hard to explain the necessity of a contextual 3D model.

Models of the build environment are also not yet at simple to deploy and therefore limited for members of the public to engage with. Nevertheless, as the digital platforms mature, we can expect this to become easier over time.

What does this mean for public engagement?

There’s currently a big push towards more engaging and innovative engagement tools and methods. Engagement events aid the specification of the project. Relationship building with the community fortifies project development from public backlash. Developers are moving beyond singular engagement events to reach out to external stakeholders.

Public Engagement is now becoming a responsibility integrated into the plan of works and has been noted as an effective project strategy within RIBA. Alongside that process, we see an increasing range of digital methods and tools for planners and developers alike to communicate with external participants. 3d visualisations play an increasing role for the ease with which they can make apparent current built environment conditions and potential future alterations. Photogrammetry, simply put, can be a great starting model for an initial consultation, to engage the public about their community.

While photogrammetry is an amazing process which configures two-dimensional images into 3D models for analysis, its production can be restricted by a user's access to imagery, time and resources.

The role of built environment models still needs further definition.

If there is interest in planning to create a 3D model for consultations, such as the aerial photogrammetry model, it will most likely be used for a consultation reviewing the current environment, and aiding the public with a visual prompt (i.e. a heritage or environmental consultation). Nevertheless, for a model to be fully owned by a project team, the visual data (aerial photography, ordinary photography) collected for its use must be owned by its creators. This is why, while photogrammetry can be simply compiled by certain software, it requires a professional hand to collect aerial photography.

The creation of a model representing the area is a collaborative effort, it requires investment, time, data, and interest to renovate the model. Due to its expense, large-scale models might be best embedded in a Council’s consultation strategy. In large-scale modelling projects such as the Northumbria and Gateshead virtual model, both local authorities worked together to cover the price for the creation of the model.

Send us your thoughts or get in touch for advice on using 3D visualisations to engage the public.

About Megan

Megan Marie Doherty is completing a PhD at Northumbria University on the ‘Design and Evaluation of Building Information Modelling capabilities for public consultation in urban planning and master planning’. Megan Doherty has a background in public engagement from previous roles in media and heritage organisations.

You can follow Megan here: @m3ganmdoherty